Edwin Thomas Beach His service in World War I |

|

| After it was all over, he didn't want to talk about the war. And then he died on February 17, 1942, leaving behind a widow and four children under the age of 12. The opportunity to hear a firsthand account of what happened to him "over there" was lost forever, but this timeline may help us understand it. |

The thumbnail at left is Edwin's entry in the US Adjutant General’s record of Ohio Soldiers, Sailors and Marines, World War, 1917-1918. It does not appear to be entirely accurate. The transcription/translation below is easier to understand. The thumbnail on the right lists the active dates for the battle sectors that he participated in.

Beach, Edwin Thomas USMC Alliance, Ohio July 6,1917

[Enlistment date] [Arrival/joining dates

for different units/locations] Character Excellent |

The muster rolls tend to not say too much about

Edwin himself; apparently he did his work diligently without drawing

a lot of attention to himself. But the comments about other

people help create a general impression of what was going on, and

it's an interesting read. The muster rolls are large images, so be

prepared to do a lot of zooming in to make the print big enough to

read. Some of the muster rolls have interesting notes from the

commander at the end. |

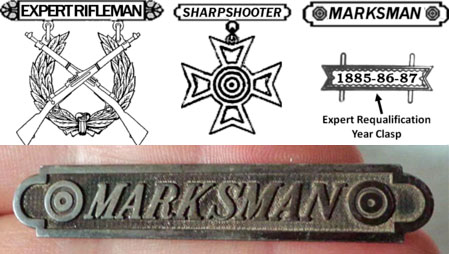

The location on the August muster roll is still the Company M Recruit Depot, Marine Barracks, Philadelphia. It shows Edwin's name and enlistment date but has no additional notes on him. The commander's note says "Names of men borne on this roll with the exception of transferred men and Numbers 106 and 117, were on Detached Duty at Marine Corps Rifle Range, Winthrop M.D. From 29th to 31st." September 7, 1917: Edwin qualified as MM (marksman) according to the first September muster roll. There were three levels of special qualifications in shooting skills. From lowest to highest, they were Marksman, Sharpshooter, and Expert. These designations were for marksmanship with rifles and/or pistols. McClellan page 69 says that 38% of the men who joined the Marines in 1917 achieved some kind of marksmanship classification, with the marksmen outnumbering the higher classifications. It also says that only men who qualified as marksman or better could be sent overseas. This was not related to machine guns; machine gunnery was a special skill, and not everyone received the training for it. The documents available to me don't mention his machine gun training, but the amount of time that Edwin spent at Quantico later on indicates that he got his machine gun training there. September 18, 1917: Edwin is transferred to the 106th Co 8th Regiment, Marine Barracks, Philadelphia, along with most of the other men in his group. The first September muster roll records his departure from his old unit, and the second September muster roll records his arrival in his new unit. |

November 1917: Edwin was on furlough from

November 4-8. On November 9, he is officially transferred to a

provisional battalion at the 34th Company Marine Barracks at

Quantico, Virginia. After the transfer, he was still on furlough

from November 9-14.

McClellan page 26 reports that the training at Quantico:

December 1917: Edwin is still at the 34th Company Marine Barracks at Quantico, Virginia. He is listed on the muster roll but there are no comments about him. |

February 1918: There has been a major change. The unit's title on the muster roll is now the 34th Company 1st Replacement Battalion, A.E.F. (American Expeditionary Forces), France. The muster roll is strangely silent about the unit's transfer to Europe, but the Doughboy Center reports that Edwin arrived in Brest, France aboard the USS Von Steuben on February 24, 1918. McClellan page 34 more or less agrees, saying that the First Replacement Battalion embarked from the US on February 5 on the Von Steuben and disembarked in France on February 25. Many of the other crossings were made in about two weeks, so it's not clear why this one (and a few others) took three weeks. The Von Steuben was a ship with a checkered past. The steamship was a German luxury liner called the Kronprinz Wilhelm from 1901-1914, then was an auxiliary cruiser in the German navy from 1914-1915 that captured 15 ships and sank 13 of them. But in April 1915 the ship was running low on coal and the crew was sick from malnutrition, so they had to seek help at the nearest port which happened to be Newport News, Virginia. The ship was interned by the U.S. government until the U.S. declared war on Germany in 1917. At this point the ship was officially seized by the U.S., renamed the Von Steuben, and used as a troop transport and supply ship to support the war effort against the ship's former home country. (Wikipedia) Most of the men including Edwin have a small star next to their name on the February muster roll. It is not clear what this means. There are no other comments about Edwin. March 28, 1918: Edwin is transferred from the Replacement Battalion to the 23rd Company of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, along with a number of other men from the Replacement Battalion. For the first time, the muster roll shows a number next to each man's name. Edwin's number is 108643. The Marines did not start issuing official service numbers until after World War I (Wikipedia), but this number apparently served a similar purpose. The Army started using service numbers in 1918, and Edwin's unit was attached to the Army's Second Division. So the Army may have assigned the number to him. This same number appears in the Adjutant General's record that was posted earlier. The March muster roll notes say "March 1-16 at Breuvannes, France; 17-28 at Ancemont, France; 29-30 in front line trenches in Chatillon and Bourbaki Sectors." Edwin went straight to the trenches when he was assigned to the 23rd Company. The 4th Marine Brigade in WWI reports that the units were ordered to move to a new area on March 14, and on March 16 they marched to a railroad station in Breauvannes, and were delivered to Lemmes in the Verdun sector. On the 17th each company was assigned to a unit to support, with the 23rd Company assigned to the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment (2/5 for short). On March 29-30 the 23rd Company relieved the French in the front line trenches, supporting the 2/5 in the Chatillon-Bourbaki Sector. History of the Sixth Machine Gun Battalion page 9 says that "At 4:00 a.m., on March 29th, the 23rd Company marched from Ancemont to Camp Rienieu, where a halt was made until 7:30 p.m., when the march was resumed to the Chatillon-Bourbaki Sector, where it relieved the French in the front line trenches, supporting the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines." McClellan page 28 says that "the average Marine who arrived in France received at least six weeks training in the United States in a recruit depot and a very short period at Quantico. This is a contrast to the six months' training received by the average enlisted man of the Army. After arrival in France the Marines, except those of the original Fourth Brigade, received practically no training in a training area since they joined the brigade almost immediately."Edwin was at the recruit depot for about 9 weeks, followed by another 3 weeks in Philadelphia as part of the 106th Co 8th Regiment. This was followed by about 18 weeks at Quantico. Then he was in France for about a month before he was transferred to the 6th Machine Gun Battalion. This was a much longer training period than average, so presumably he received his machine gun training at Quantico. Wikipedia reports that the training of the original members of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion lasted for about 3½ months at Quantico, and included weapon familiarization, pillbox construction, fire discipline and trench warfare doctrine. In March 1918, a special school for machine gun training was set up in Utica, New York, but Edwin was already in France. |

|

Organizational information. The 1st Machine Gun Battalion was formed at Quantico in August 1917, and was renamed the 6th Machine Gun Battalion on January 15, 1918. The original members of the unit trained at Quantico until they shipped out for France in mid-December 1917, and continued training there. On March 15, 1918 (about two weeks before Edwin was transferred in), the battalion was sent to the front lines. The battalion consisted of a headquarters company

and four battle companies: the 15th (A) Company, the 23rd (B)

Company, the 77th (C) Company, and the 81st (D) Company. The 15th

and 23rd Companies were originally part of the 5th Marine Regiment,

but in January 1918 they were detached from this regiment and assigned

permanently to the 6th Machine Gun Battalion. The

Doughboy Center explains the organization of the machine gun

battalions and their battle tactics:

"The machine gun company, commanded by a captain, had an assigned strength of six commissioned officers and 172

enlisted men, and carried 16 guns, four of which were spares. Within the company there were three platoons and a

headquarters section. A first lieutenant led the first platoon, while second lieutenants led platoons two and three.

Each platoon with four guns was made up of two sections, each having two guns and led by a sergeant. Within each section

were two gun squads, each with one gun and nine men, led by corporals. The gun squad had one combat cart, pulled by a mule,

to transport its gun and ammunition as close to the firing position as enemy fire allowed. From there the crews moved the

guns and ammunition forward by hand... "Since the usual plan of maneuver of an infantry battalion called for three of its four rifle companies to be used as the

attacking force, with the fourth company serving as a reserve, the machine gun company commander would usually place one of

his three machine gun platoons in support of each maneuver company.

"Machine guns were used for both indirect and direct fire missions. When in the former role, the guns were placed to cooperate

with the field artillery units in neutralizing suspected enemy observation posts and machine guns during the attack and to sweep

the approaches for possible enemy counterattacks after the capture of the final objective.

"The guns were most effectively used in overhead fire missions to support the infantry attacks. In this role the guns were placed

300 to 1000 meters to the rear of the front line. When they employed their guns in that fashion, the machine gun officers often ran into

opposition from the rifle company commanders, who preferred to have the guns farther forward, fearing that their infantrymen would be at

risk of stray low rounds as they advanced under the overhead machine gun fire. However, over time the infantrymen came to accept this

arrangement as they saw the reliability of the machine guns proved again and again in combat. Furthermore, they soon discovered that the

machine guns were high priority targets for enemy fire, and that it was advantageous to have the guns at some distance from the infantry positions. "Since enemy machine guns posed the greatest threat to the attacking troops, the machine gun crews made every effort to locate the enemy guns

and to concentrate their fire upon them. As the attack moved forward and the overhead fire became less effective, some of the gun squads would

carry their guns and ammunition forward either into or on the flanks of the advancing infantry. A proportion of the guns was held back as a

reserve under command of the machine gun officer.

"Machine gun tactical doctrine dictated that in the defense the Hotchkiss guns should only rarely be located within 100 yards of the front line

and that at least two-thirds of the guns should be echeloned back through the whole defensive position, located so that adjacent guns would be

mutually supporting. From such positions all guns could fire in defense of the front line, and in the event of an enemy breakthrough the rear guns

could continue to defend even if the enemy overran the forward guns." In other words, each company had 12 machine gun crews (four gun crews per platoon). As described above, it was common for infantry battalions to put three companies into action during battles and hold the fourth in reserve; and the reports from machine gun company commanders (discussed later) indicate that it was also common to hold some of the machine gun crews in reserve during battles, by company, by platoon, or whatever system best served the purpose at the time. For more information on the organization of a machine gun company, click this link and go to page 348 of Organization of the American Expeditionary Forces to see Table 8. It's so detailed that they even tell you how many bicycles a machine gun company had. All the major Marine combat units in World War I were part of the 4th Marine Brigade, which consisted of the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments and the 6th Machine Gun Battalion. McClellan page 29 has a chart with more information on the organization of this brigade, and page 38 shows the organization of the entire 2nd Division. The 4th Marine Brigade was one of two infantry brigades in the 2nd Division of the US Army. The machine gun battalion was designed so that all its companies could be deployed together as a single unit, or the companies could be deployed separately to support specific infantry units. When they were deployed separately, the 23rd company was usually assigned to the 2nd Battalion of the 5th Marine Regiment (the 2/5 for short). The battalion used Model 1914 Hotchkiss machine guns. Monongahela Books has a site dedicated to the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, with a nice collection of pictures of the equipment, a photo gallery including a picture of Edwin and other pictures from the front, uniform pictures including Edwin's, and a variety of other features. Together We Served provides the additional information that Edwin's last primary MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) was 0333 Heavy Machine Gunner. They have a list of 65 other men who served in the 23rd Company at the same time, and only three others are MOS 0333. Two are 0332 (also Heavy Machine Gunner). Five men are are 0331 (Machine Gunner, without the "heavy" designation), and eight are 0311 (Rifleman). Forty-two of the men on the list don't have an MOS designation, indicating that they weren't specialists. There's also a cook (3371), a clerk (0151), and a drummer (5563). The list is obviously incomplete, since each company had 172 enlisted men and 6 commissioned officers. Each company had twelve active guns, and each gun was attended by a crew of 9 men commanded by a corporal. Each crew obviously needed at least one man to actually fire the gun, and maybe a backup or two in case anything happened to him. But they also needed additional men to help carry the equipment, set up the gun, and pass the ammunition.

The 0333 classification no longer

exists, and I couldn't find any additional information on it. In the modern

Marine Corps, heavy machine gunners are MOS 0331, and it's reported

that they are usually bigger, stronger individuals because of the

strength required to carry the equipment (Careers).

This was probably as true in World War I as it is today. At 5'8¼",

Edwin wasn't particularly big, but he was obviously strong enough to

handle the work. |

Toulon Sector (Verdun), March 30-May 13, 1918: Verdun was the site of one of the biggest, longest, bloodiest battles of the war in 1916, but it was considered to be a quiet defensive sector in 1918. But it was still part of the front line, and it was a good place for men who had never been on the front before to get their first taste of actual field conditions. There were no major engagements here during this time period, but there were a number of raids and enough action that activities like the digging of machine gun emplacements had to be done after dark to avoid enemy fire. Page 48 of Devil Dogs says, "While in the Verdun sector the companies of the battalion were constantly on the move to and from their designated areas and suffered ten casualties." History of the Sixth Machine Gun Battalion page 11 shows that the casualties were 1 killed, 1 wounded, and 8 gassed. All were from the 15th company, except that one of the gassed was from the 81st company. The general plan during this time period was for each battalion to spend 10 days on the front and then be relieved for 10 days. The men had to do a lot of digging during their 10-day "rest" period. History of the Sixth Machine Gun Battalion page 11 says "During the period of service in the front line trenches in this sector the companies participated in repelling raids, patrolling No-mans land, repairing barbed wire, constructing trenches and machine gun emplacements, indirect fire, barrage fire and harassing fire." The April muster roll notes say "April 1-30, in front line trenches in Chatillon and Bourbaki Sectors, France". It also reports that Edwin's marksman insignia was delivered on April 17. The May muster roll doesn't comment on him.

Devil Dogs page 44 reports that getting food to the men on the front lines was a difficult undertaking. The enlisted men on the front lines never got enough to eat or drink, and when the food arrived it was cold and of poor quality. But alcohol was overly abundant, and there were issues with drunkenness. Conditions on the front lines were hard on the uniforms, and ragged clothing was common. The trenches were muddy and cold, which caused an unpleasant condition called trench foot, and they were heavily infested with lice (NCpedia). Trench life was no picnic even when nobody was shooting at you. The May muster roll notes say "1-13 in front line trenches in Chatillon and Boubaki Sectors, France; 14, at Heippes France; 15 at Hargeville, France; 23-31 at Montjavault, France." On May 14th the 4th Brigade relocated to the vicinity of Chaumont en Vixen. They traveled by train and with a two-day road march, with troops billeted in barns and farmyards along the way. Intensive training was undertaken there in anticipation of being assigned to an active front. The 6th Machine Gun Battalion was deployed as a single unit so they could provide concentrated fire support at key points along the Allied line during both defensive and offensive operations. The 15th and 23rd companies were assigned to the left flank of the Allied line, and the 77th and 81st to the right. History of the Sixth Machine Gun Battalion page 10 says "The 23rd Company was relieved the night of May 13-14th, by the French in Chatillon-Bourbaki Sector, and marched to Ancemont." It goes on to report that on May 14th from 7 AM to 3 PM, the entire battalion marched 17 kilometers from Ancemont to Hieppes and billeted for the night; on May 15th from 8 AM to 4 PM they marched 20 kilometers from Hieppes to Hargeville and billeted; on May 16th from 8 AM to 9:30 PM they marched 40 kilometers from Hargeville to Venault-le-Chatel, where they rested until May 20th. On May 20th they marched from 9 AM to noon, traveling to Vitry-le-Francois. All but the 15th and 23rd companies left at 4:30 PM, but the 15th and 23rd stayed longer and left for Isle-Adam at 9:30 PM. The wording is a bit unclear, but it sounds like everyone was traveling by train instead of marching, and the first train may not have had enough room for everyone. The 15th and 23rd companies arrived at Isle-Adam at 9 AM on May 21, then marched 22 kilometers to Haravillers. On May 22nd, the 23rd, Headquarters and Supply Train companies left at 8 AM and marched 15 kilometers to Montjavoult and billeted there, while the rest of the battalion marched to other nearby destinations. History of the Sixth Machine Gun Battalion page 12 reports that in the Montjavoult training area The battalion remained in place drilling, refitting and reorganizing. Considerable exercises were held in open warfare. Companies were trained in section movements; taking up positions; company movements; placing machine guns in forward and rear groups; batteries of 4 guns each and 2 companies in a group; nomenclature of machine guns; organization and direction of fire, and defense against gas... Orders received from Headquarters, Second Diviion, that the Division would move to a new area on May 31st, and the battalion would hold itself in readiness to move." |

Wikipedia is currently reporting that during the night of June 1, the 23rd Infantry Regiment, the 1st Battalion of the 5th Marines, and an unidentified "element" of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion conducted a forced march over 10 km (6.2 mi) to plug a gap in the line, which they achieved by dawn. But page 78 of Devil Dogs says that it was the 5th Machine Gun Battalion that was involved in this action, not the 6th, and they are probably correct.

Page 142 of At Belleau Wood reports that the battle plan called for the 23rd Company to support the 1st Battalion 5th Marines' attack on Hill 142 beginning at 3:45 AM. But the orders were not delivered on time and things did not go as planned. Several companies were not in the right place at the appointed hour, and there was no sign of several others including the 23rd Company. Devil Dogs page 100 says the orders came too late for the 23rd to make it there on time. The 1/5's attack on Hill 142 went forward using 10 guns of the 15th Company, but without the 23rd Company. By 5 PM, the 23rd Company was in position on the western edge of Belleau Wood supporting the 3rd battalion of the 6th regiment (3/6). On June 6 Edwin was exposed to mustard gas, but it wasn't severe enough to put him out of action. In addition to harming the respiratory system, mustard gas can cause chemical burns and blisters on the skin, digestive symptoms including vomiting and diarrhea, and decreased red and white blood cell counts (CDC). The June 1918 muster roll doesn't mention the gas, in fact it doesn't comment on Edwin at all, although it lists a number of casualties and the arrival of replacements. The July muster roll doesn't comment on him either. He was awarded the Purple Heart for this incident in 1989, at the request of the family. Devil Dogs page 101 calls this day "the most catastrophic day in Marine Corps history" because of the high casualties. The 2nd Battalion 5th Marines (2/5 for short) that the 23rd Company was usually attached to was not involved in the main action that day, and instead the 23rd Company was supporting the 3/6. The 3/6 had to advance through a waist-high wheatfield into enemy machine gun fire during this attack, and also faced sharpshooters and barbed wire. The machine gunners also had to move forward periodically as the line advanced. On June 7 the company was involved in the battle for

Hill 142, which was occupied by the 1/5 at the time.

Devil Dogs page 130 says "German soldiers were assembling in and

around Torcy, but fire from the 23rd Machine Gun Company succeeded

in breaking them up and repelling an attack" on hill 142.

The 2/5 was ordered proceed down the Lucy-Torcy Road at night, but

the orders were based on a misunderstanding of where some other

units were. This led to the 2/5 being fired on by both the Germans

and the Americans, with several casualties (Devil Dogs

page 131-133). "In the morning of 10 June, Major Hughes' 1st Battalion, 6th Marines—together with elements of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion—attacked north into the wood. [According to The 4th Marine Brigade in WWI, this "element" included six of the 23rd Company's twelve guns]. Although this attack initially seemed to be succeeding, it was also stopped by machine gun fire. The commander of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion—Major Cole—was mortally wounded. Captain Harlan Major—senior captain present with the battalion—took command. The Germans used great quantities of mustard gas. Next, Wise's 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines was ordered to attack the woods from the west, while Hughes continued his advance from the south. On June 12 the 2/5 was involved in heavy fighting in an attempt to take the entire Woods. The attempt did not succeed, although they did hold on to the northeast part and continued to hold that position until they were relieved on June 15. The 1/6 was also still fighting on June 11-12. We don't have specific information on what gun crews of the 23rd Company were doing, but it appears that the four guns with the 2/5 and the six guns with the 1/6 stayed with these units and continued to participate in the fighting. The final push to take the woods on June 24-26 involved the 2/5, but their machine gun support isn't specified. The 23rd and 77th companies had already been relieved, but the15th and 81st remained on duty until June 28 and June 29, respectively. For the period from June 27 to July 5, Devil Dogs page 203-204 says that this period was a time of minor action, but "Guns of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, supplemented by the division's 4th Machine Gun Battalion, remained in place to support the 4th Brigade, with two companies on line and two out". In contrast, The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I says that by June 30, all the 6th MGB companies were at rest, and their replacements (mostly from the 4th Machine Gun Battalion) were working under the command of the 6th MGB commander. The best timelines for the 23rd Company comes from

The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I and the

History of the Sixth Machine Gun Battalion has a similar account.

Unfortunately these sources do not have a company commander's report for this battle

The 23rd Company's June muster roll notes say "Served in open warfare against the enemy in the Belleau Woods, Chateau-Thierry sector fr 1 Jun 18 to 20 Jun 18."

McClellan page 41 sums things up rather nicely:

"The fighting of the Second Division in the Chateau-Thierry sector was divided into two parts,

one a magnificently stubborn defensive lasting a week and the other a vicious offensive. The defensive

fighting of the Second Division between May 31 and June 5, 1918, was part of the major operation called by the Americans the Aisne defensive. "On June 6, 1918, the Second Division snatched the initiative

from the Germans and started an offensive on its front which did

not end until July 1, 1918. The Marine Brigade captured Hill 142

and Bouresches on June 6, 1918, and in the words of Gen.

Pershing, 'sturdily held its ground against the enemy's best

guard divisions', and completely cleared Bois de Belleau of the

enemy on June 26, 1918, a major of Marines sending in his famous

message: 'Woods now U.S. Marine Corps' entirely'. The American

commander in chief in his first report calls this fighting 'the

battle of Belleau Wood' and states, 'our men proved their

superiority, and gained a strong tactical position with far

greater loss to the enemy than to ourselves'. In his final

report he states: 'The enemy having been halted, the Second

Division commenced a series of vigorous attacks on June 4, which

resulted in the capture of Belleau Woods [on June 26] after very

severe fighting.... In these operations the Second Division met

with most desperate resistance by Germany's best troops'. "During these 31 days of constant fighting, the last 26 of

which has been defined by general headquarters of the

American Expeditionary Forces as a "local engagement," the

Second Division suffered

1,811 battle deaths (of which approximately 1,062 were

Marines) and suffered additional casualties amounting to

7,252 (of which approximately 3,615 were Marines). It was

that fighting and those 9,063 casualties that first made the

name Chateau-Thierry famous.

"The achievements of the Fourth Brigade of Marines in the

Chateau-Thierry sector was twice recognized by the French.

The first, which changed the name of the Bois de Belleau,

was a beautiful tribute spontaneously made to the successes

and to the losses of the Fourth Brigade of Marines, and

shows the deep effect that the retaking of Belleau Wood and

other near-by positions from the Germans had on the feelings

of the French and the morale of the Allies. Official maps

were immediately modified to conform with the provisions of

the order, the plan directeur used in later operations

bearing the name "Bois de la Brigade de Marine." The French

also used this new name in their orders. The second recognition by the French was a laudatory statement that was not translated into English in the text. On a more visible level, the French later awarded the 4th Marine Brigade the fourragère of the Croix de Guerre for their accomplishments at Belleau Wood, Soissons, and Blanc Mont Ridge. On an informal level, the brigade earned the nickname "Devil Dogs" with the fierceness of their fighting at Belleau Wood. However, it's suspected that the name is an American invention and not something that the Germans actually called the Marines at Belleau Wood (ThoughtCo). History of the Sixth Machine Gun Battalion says that for the first three days of this battle, "all the companies were thrown almost entirely on their own resources as far as food was concerned, this being due to the fact that the animal transportation had not caught up to the battalion. The rapid advance of the Huns caused much stock to be abandoned by the refugees. Stock wandered all over the country occupied by our troops, and owing to the shortage of rations the stray cattle and hogs were butchered and the meat distributed to the men." It also reports that The supply of ammunition was excellent and reliable, at all times. Several machine guns with their entire crews were destroyed by shell fire. Ten mules were killed by shell fire." |

The July muster roll was displayed in the

previous section.

On July 16th, the 2nd Division was ordered to move toward the city of Soissons (which the Germans had taken on May 27 in the prelude to Belleau Wood) in order to launch a counter-assault. The 4th Marine Brigade made the journey in camions. The 6th Machine Gun Battalion arrived at their destination at about 3 AM on the morning of July 18, hours later than the rest of the troops, and without their guns, which were traveling separately. The guns finally arrived late in the afternoon of July 18, when the battle was already well underway. The 4th Marine Brigade in WWI says that records of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion are scarce for this campaign. The battalion arrived in exhausted condition at the north end of the Bois de la Retz on July 18 and rested there for a while. At noon the 23rd Company was ordered to support the 2/5 (which was heavily engaged in the combat). But apparently this didn't happen, and at 2100 they received new orders to join the Army's 23rd Infantry. The other machine gun companies were also assigned to Army infantry units, but it's not clear how much fighting they did that day. The infantry moved forward so fast that the machine gun companies had a hard time keeping up while carrying their heavy guns.

The fighting was so

fierce, and the troops so exhausted and short of food, that by the

end of the day the regiments that had been fighting were no longer

combat effective. The attack on the next day, July 19, was

made by the 6th Marines and the 6th Machine Gun Battalion. The

6th Marines had not participated in the previous day's battle, and

apparently the 6th MGB was also relatively fresh.

The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I

says that the 15th Company was initially assigned to the 3/6 on July

19, but at 1600 they received orders to go elsewhere, and the 23rd

Company replaced them (apparently supporting the 3/6). "Although the machine gunners were unable to contribute much to the attack on the 18th they were way up front on the 19th. The 81st Company, with two platoons from the 77th Company, were just west of and facing Tigny while the 15th protected the northern side of Vierzy, facing Charantigny. The balance of the 77th and headquarters of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion took up positions in Vierzy and the 23rd Company was posted to their front. The 81st had one officer killed in action, Capt. Allen M. Sumner; so was 2d Lt. Herbert K. Jones, USA of the 23d. The battalion's total enlisted casualties numbered eight killed and forty-three wounded." The casualties were much higher among the infantry, and the 6th Marines lost more than half their men that day. McClellan page 45 sums the battle up for us: "Of the six Allied offensives taking place in 1918 on the Western Front, designated by the Americans as major operations, the Fourth Brigade of Marines, with the other units of the Second Division, participated in three, the first being the vast offensive known as the Aisne-Marne, in which the Marine Brigade entered the line near Soissons. The 4th Brigade was relieved by French troops at 0100 on July 20 (The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I). The 6th MGB marched to the woods at Carrefour de la Croix and bivouacked. They remained in a reserve position until July 22, then marched to an area further in the rear, although officially they were still in a reserve position. After final relief from this active sector on July 24 they were billeted in an area around Nanteuil-le-Haudouin, halfway between Soissons and Paris, where they remained until July 31. Then they had a 24-hour railroad journey to an area around Nancy, where they rested for a few more days. The July muster roll notes say "Except as otherwise stated in “Remarks”, I hereby certify that each man whose name appears herein served in open warfare against the enemy in the vicinity of the town of Vieray, France from 17th to 20th inclusive." |

| The muster rolls for August

and September 1918 are different than the others. Instead of

listing all the men, they are "supplemental" rolls that only seem to

show show the men who were

being written up for some reason (exceptional service, rule

violations, transfers, etc). Edwin's name does not appear on

the rolls for these months.

Marbache sector, August 9-16, 1918:

Although officially designated as a battle zone because it was on

the front lines, there wasn't a lot that actually happened in this

sector during

this time period. An

enemy raid was successfully repulsed, but otherwise it was

considered to be relatively quiet and

uneventful, even though the German artillery was quite active (McClellan

page 48,

Devil Dogs

page 263). During this time the companies of the 6th MGB were

divided up amongst the infantry battalions, with the 23rd Company

getting their usual assignment with the 2nd Battalion 5th Marines

(2/5) (Devil Dogs

page 263). Devil Dogs page 265 reports that during this time period, the potatoes in the Marines' diet were temporarily replaced by tomatoes, which were overabundant in the area. This change was welcomed at first, but it wasn't long before they wanted the potatoes back again. The units of the brigade started moving toward the Marbache subsector, near Pont-a-Mousson on the Moselle River on August 5, and completed the move by August 8. Their relief from this sector was completed on August 18 and the brigade moved to an area near Toul for intensive training for the upcoming St. Mihiel offensive. Devil Dogs page 268 says "The 6th Machine Gun Battalion was assembled with the regimental machine gun companies. Together with the entire divisional machine-gun units, they were engaged in a special training exercise at the same camp." |

| Edwin does not appear on the September

muster roll - see note in previous section. St. Mihiel Offensive, September 12-16, 1918: The division was on the move again starting on September 2 with a series of night marches that were designed to conceal their movements from the Germans. The St. Mihiel salient had been in German hands since the start of the war, and the French had been unable to dislodge them. General Pershing had been wanting to take it since his arrival in France, and now the time had come. The 2nd Division (along with the 6th MGB) arrived on at St. Mihiel on September 11 and the battle began the following morning. The plan on the first day (September 12) called for two Army regiments to advance, supported by the Marines, with the 23rd Machine Gun Company bringing up the rear on the right flank. But things didn't go quite as planned. Unbeknownst to the Allies, the Germans had already begun withdrawing from the area and were not at full strength. So the Army infantry was able to move faster than expected, and the 23rd Machine Gun Company moved right behind them to provide support, leaving their own 2/5 behind even though they were supposed to be moving together. The 2/5 eventually caught up and rejoined the 23rd Company. The reporting on the 6th MGB from most sources is rather sparse, but Devil Dogs page 277 says that on Day 2 (September 13), the 6th Machine Gun Battalion was assigned to barrage positions north of the Flirey—Pont-a-Mousson road to support the attack of the division. WWI Centennial says "On the evening of the 13th, the Marine Brigade took over the entire front line of the advance. During the rest of the operation, the task of the Marines was to drive back the German outposts in front of the St. Mihiel position."

The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I has

detailed reports from the commanders of each company. The 23rd Company's

report included this information:

Wikipedia sums up the battle for us:

Pershing's plan had tanks supporting the advancing infantry, with two tank companies interspersed into a depth of at least three lines, and a third tank company in reserve. The result of the detailed planning was an almost unopposed assault into the salient. The American I Corps reached its first day's objective before noon, and the second day's objective by late afternoon of the second. The attack went so well on 12 September that Pershing ordered a speedup in the offensive. By the morning of 13 September, the 1st Division, advancing from the east, joined up with the 26th Division, moving in from the west, and before evening all objectives in the salient had been captured. At this point, Pershing halted further advances so that American units could be withdrawn for the coming Meuse-Argonne Offensive." The operation was a cakewalk compared to what they'd expected, but there were heavy casualties nonetheless. Devil Dogs page 285 says "it is evident that the dead and wounded were mainly from the 6th Marines and the 6th Machine Gun Battalion". It says that the 6th MGB had 41 wounded, but does not mention deaths. Casualties were considerably higher among the Marine infantry. The detailed reports in The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I say that the 77th and 81st companies saw more fighting than the 15th and 23rd did. The 4th Brigade was relieved on the night of September 15-16, except that the 6th Machine Gun Battalion stayed in place for another 24 hours. On September 20, the brigade moved to an area south of Toul and remained in this area until September 25, when it moved by rail to an area south of Chalons-sur-Marne. |

During this battle the machine gun companies were assigned to specific Marine battalions, with the 23rd Company getting their usual assignment with the 2/5. They were positioned on the right flank. The battle was a hard uphill fight against a nearly impregnable position. The attack began on October 3, with the 6th Marines initially taking the toughest approach and the 5th Marines having a relatively easy time. Late in the day, the order was given for the 5th Marines to pass through the 6th Marines to the front line and continue the attack. But the day's fighting had left the units too spread out and disorganized for this to happen, so the remainder of the day's attack had to be canceled. The battle resumed the next morning (October 4) with the 5th Marines leading the way. The 3/5 was in front, followed by 1/5, with the 2/5 bringing up the rear as a regimental reserve. All three battalions were subjected to ferocious artillery and machine gun fire as they traveled over broken ground. After about a mile they were forced to stop, and were ordered to dig in where they were. Devil Dogs page 311 says that the 77th Machine Gun Company was with the 3/5 providing some protection, but does not say where the other machine gun companies were. The 5th Marines were so badly damaged by this day's fighting that they did not participate in the rest of the Blanc Mont campaign. The battle continued for another 5 days of fierce fighting until it was finally won on October 9. Wikipedia says, "the 6th Machine Gun Battalion's companies laid down a heavy suppressing fire as both the 4th Marine Brigade and the French 4th Army stormed Blanc Mont ridge". There is no specific information on the 23rd Machine Gun Company, but they apparently continued to fight during this period. Devil Dogs page 336 says that all the companies of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion "were always up front with the attacking groups, suffering accordingly" during the entire Blanc Mont fight, and that the battle "was a relatively short period, compared to the Belleau Wood campaign, but it was as intense and as bloody and, according to the veterans of both, worse." The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I has a detailed report on the 23rd Company from October 1-10:

There is a separate report by the battalion commander that tells the same story, as well as reporting on what the other three machine gun companies were doing. The 23rd and the 77th saw the most action. The report states that the relief of the 6th MGB was badly bungled, since the relieving division had no orders, instructions, or idea of what they were to do. The commander of the machine gun battalion that was relieving the 6th MGB was never seen and could not be located. The October 1918 muster roll doesn't make any comments about Edwin, but it shows many replacements joining the 23rd Company after the battle. The company must have had heavy casualties. From October 10 to October 31 the 4th Brigade stayed in a variety of places for a few days at a time, often marching from place to place. Devil Dogs

page 343 does not

specifically mention the 6th MGB, but it reports the following

movements for the 2nd Division in general: |

Meuse-Argonne Offensive Nov 1-11, 1918: The 4th Brigade went back into combat on the morning of November 1, joining the last phase of the massive Meuse-Argonne offensive that had been underway since September 26 Wikipedia says that the companies of the 6th Machine Gun Battalion were kept together as a single unit, but other sources indicate that this is incorrect; they kept to their usual pattern of specific companies supporting specific regiments. The battle began with a two-hour Allied artillery barrage that included heavy fire from the entire 6th MGB (Devil Dogs page 349). The barrage was effective enough that the infantry attack that followed it encountered relatively little resistance. As the Germans were pushed back, the machine gun battalion advanced along with the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments toward the Meuse River. By November 5, some of the American forces had started to cross the Meuse, 30 km from the point where they began on November 1. But most of the troops including the 4th Brigade were delayed from crossing the river by the lack of bridging equipment, and the traffic congestion to their rear interfered with the delivery of other supplies. The Germans were fiercely defending the crossing points to protect the retreat of their own army. On November 10, the 5th and 6th Marines were ordered to cross the river and take a heavily defended ridge, and some machine gun crews went with them. The description of the timing in Devil Dogs is rather garbled, but apparently a pontoon bridge was built and the river was crossed around midnight during the night of November 10-11, with heavy casualties. Devil Dogs page 374 says: "The 23rd Machine Gun Company... was assigned to cross with the 5th Marines, but only one gun and crew survived. After arrival on the eastern bank they set up and defended the bridge, so that if the Marines were forced to retire they could use the badly shattered link with the western side. If they couldn't cross that flimsy wreck of a bridge, they could swim." Was Edwin Beach the gunner for that solitary machine gun emplacement? Based on the detailed report from the 23rd Company commander in The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I, it seems mostly likely that his gun crew started out in a combat position during this campaign but didn't make it as far as the Meuse, dropping out on November 8 or 9. According to the report:

The report by the battalion commander tells the same story, and provides information on what the other three companies were doing. It also adds this information: "The casualties sustained by the 23rd Company near Belle Tour Farm and during the crossing of the Meuse on the Night of November 10th were heavy, but with this exception evacuations resulting from wounds were light. All companies, however, suffered heavy losses by evacuation on account of sickness. All sick men were evacuated through 5th and 6th Marines... Owing to the fact that the advance was rapid and the rear eschelon was left so far behind administrative work was maintained under the greatest difficulties." The reports on illness are significant because Edwin was sick during this time period. There is a supplemental muster roll published in August 1919 that seems to be a casualty/sickness report covering men from many different companies for most of 1918 through July 1919, reporting non-combat related health issues and relatively minor combat wounds. The report uses a lot of coding, but “FH” apparently means field hospital. The entry for Edwin says “23rd Co: FH#1 11/8/18 Gastro Enteritis jd fr Comd, 11/8/18 tr to FH#16, FH#16 11/10/18 jd fr FH#1, 11/10/18 tr to duty.” The commander's report says that two gun crews were evacuated for sickness on November 9, while the August 1919 report says that Edwin went to the field hospital on November 8. But the difficulty of doing administrative work at this time has been noted, so it wouldn't be surprising if one of these sources made a slight mistake in the date. Edwin returned to duty on November 10, but the commander's report indicates that the sick gun crews did not come back to participate in the Meuse crossing. Alternatively, Edwin might have been in the platoon that stayed with the liaison company and was not sent out to the Meuse crossing at all. NCpedia reports that the severely wounded were taken to base hospitals far behind the front lines, but doesn't say what happened to the minor cases. KU Medical Center says that the field hospitals functioned as emergency aid stations that did not retain patients, and instead passed them along to an evacuation hospital as quickly as possible. The November 1918 muster roll has a supplemental list of men who were sick, wounded, or killed, and Edwin's name isn't on that list. It looks like this list only covers the men who were sent to hospitals behind the lines, not the ones who were only treated at a field hospital. But Devil Dogs page 365 says that on November 8-9 "Traffic was jammed on every road into the area, so much so that even the wounded and sick could not be taken to hospitals in the area." So nobody was going anywhere - men who were already near the front were stuck there, and those in the rear were stuck there too. Edwin's records don't say that he went anywhere other than a field hospital. One of the few bits of war lore passed down through the family is that only five of the men who started out in his unit made it to the end of the war without becoming a casualty, and Edwin was one of the five. We're not sure exactly what unit was meant - the whole 23rd Company? His platoon? Something else? In any case, it looks like he lost many of his colleagues on the last day of the war. The troops were unaware that an armistice was being negotiated when the crossing of the Meuse began. But the commanders certainly knew that an armistice was being negotiated, so the day's action was a senseless waste of lives for the sake of having a slightly stronger negotiating position. Edwin's illness in the closing days of the war might have been Spanish influenza. This global pandemic ravaged the world in 1918-1919, and it's believed that troop movements and the harsh, crowded conditions at the front were a major factor in spreading it (KU Medical Center, The Conversation, Passport Health, Wikipedia). Many soldiers were affected by it, and the more virulent strain that arose in the fall of 1918 apparently originated in the trenches. The men who had been exposed to the milder form that appeared in Spring 1918 had better immunity against the new form than the ones who had never been exposed. Spanish influenza is primarily known for its severe impact on the lungs, but the disease had other forms and one of them had gastric effects instead of attacking the lungs (Erkoreka). The man below Edwin on the postwar report went to the field hospital at about the same time for the same complaint. Devil Dogs page 359 reports that many men in the division were sick or dying from the flu during this final campaign. The Germans were impacted by it too, maybe even more than the Allies, and it may have hastened their decision to surrender. The only mention of Edwin on the November muster roll is this: it shows him as a corporal for the first time, and says "22 pmtd to Cpl, T. Foreign W. to rank as #5 fr same date, auth Bn. Comdr." Several other men on the page have the same note with a different number. His last name is blurred, and the Ancestry computer transcriptionist read it as Edwin T Boach. Use that name to search for this document in Ancestry's document library.

|

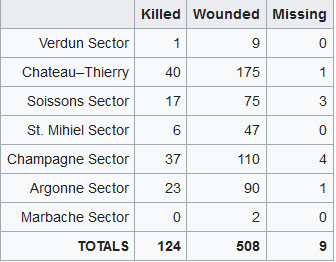

Major Engagements and Casualties: From McClellan page 58: “General Headquarters, American Expeditionary Forces, ruled that the Second Division, including the Fourth Brigade of Marines, participated in only four major operations, the Aisne defensive (May 31 to June 5, 1918); the Aisne-Marne offensive (July 18 and 19, 1918); the St. Mihiel offensive (Sept. 12 to 16, 1918); and the Meuse-Argonne offensive (Oct. 1 to 10, 1918, and Nov. 1 to 10, 1918). The operations which resulted in the capture of Blanc Mont and St. Etienne were construed to be included in the Meuse-Argonne offensive despite the fact that the operations were a part of the operations of the Fourth French Army, far to the west of the western limit of the American Meuse-Argonne sector and further that the work of the Second Division was continued by another American division. The operation which resulted in the capture of Hill 142, Bouresches, Bois de la Brigade de Marine [Belleau Wood], by the Marine brigade, assisted by Artillery, Engineers, etc., of the Second Division, and the capture of Vaux by the Third Brigade, Engineers and Artillery of the Second Division, were held to be local engagements rather than a major operation. The Second Division suffered about 9,000 casualties in the Chateau-Thierry sector." They ruled that Belleau Wood was not a major engagement. I have nothing to say because this leaves me speechless. It's true that it was not an important strategic goal, and was more of a show of strength. But the fighting was very fierce, and the casualties were extremely high. McClellan page 65 has a casualty chart for the entire 4th Marine Brigade. Click on the thumbnail for a larger image. The number of men mustered out of the brigade at the end of the war was 6,677, and the total casualties were 11,612. That's a 174% casualty rate, because the casualty rate among the infantrymen of the 5th and 6th Marines was even higher than the rate among the 6th Machine Gun Battalion. The infantry often had to advance straight into enemy machine gun fire, and it was not the job of the machine gunners to do this. But the machine gunners were the most dangerous individuals on the battlefield, so they were a high priority target for the enemy. |

The 4th Marine Brigade in World War I says that the 23rd Company had been assigned to the town of Bremscheid by December 16, but they changed location to Waldbreitbach on December 23rd. The reason for the change was not given. The other three companies were assigned to three other towns, and none of them changed location. The entire battalion continued to train until they left Europe.

The muster roll notes

for November say "I

certify that all changes occurring in the status of members of this

organization are accounted for in the remarks hereon and except as

otherwise noted in column of "Remarks" all members of this

organization took part in the operations against the enemy in the

Argonne Sector, France, from November 1, 1918 to November 11, 1918,

and were members of the Army of Occupation from November 17,1918 to

November 30, 1918". The notes also say "1-17 France, 18-20

Belgium, 21-30 Luxembourg". The muster roll notes for "C"

Company go into much more detail, which apparently applies to

Edwin's company too. The C Company notes say

The muster rolls were issued regularly after the occupation began, and from January 1919 onward the set is complete except for February. The February report is one of those "supplemental" muster rolls that only lists the men who have some sort of change in their status. Edwin does not appear on it.

Edwin was promoted to Corporal on Nov 22, 1918. The December 1918 muster roll is yet another one of those "supplemental" reports that only lists the men who are being written up for some reason. It notes that everyone was in Germany from Dec 1-31. Edwin does not appear on the December muster roll. But the January 1919 muster roll says "TFW as Cpl changed to TWW Dec 18, auth letter MGC of same date". TFW means "temporary foreign warrant" according to this USMC list. They don't explain what TWW means, but it's apparently some other type of temporary warrant. I can't find information on what a temporary foreign warrant was, but this article talks about a 5th Regiment Marine who was promoted under one the month before Edwin was promoted. The March 1919 muster roll says "March 1-9 on leave in France in accordance with G.O.#14, G.H.Q., A.E.F." I hope he enjoyed it. April 1919: "April 7-30 Det’d at School, Motor Reconstruction Park, Romorantin, France, for instruction"May 1919: "May 1-31 Det’d at School, Motor Reconstruction Park, Romorantin, France. Auth S.O. #94 Hdqtrs. 2nd Div. dated 5 Apr 19"

June 1919: "June 1-4 Det’d at School, Motor Reconstruction Park, Romorantin, France" “Further refinements of the AEF’s educational programs came on February 13, 1919, with General Orders No. 30. This created divisional schools that were to teach courses at the high-school level, together with a list of fourteen designated trades. In the trade courses, men from both the post and division schools were often trained in connection with the work routinely carried out at the numerous large repair shops maintained by the army. The students were instructed by military personnel who were expert craftsmen and technicians. Some of the installations involved were the motor reconstruction park at Verneuil, the railway shops at Nevers, the motor construction park at Romorantin, the supply depot and Signal Corps shops at Gievres, the ordnance shops at Mehun, the driver and mechanics school at Decize, and the remount station at Sougy. Over four thousand soldiers were eventually involved in this training.” That wasn't Edwin's only activity during this period. His discharge papers say that he qualified as a 2nd class pistol shot on June 23, 1919. |

Going home July 1919-August 1919: Effective July 5, orders were received that transferred the 2nd Division to the Service of Supply for transportation home. Other duties were canceled so everyone could prepare to go home. Trains began carrying troops to Brest on July 15, where they boarded ships and sailed westward. The last troops arrived at Brest on July 23, and it's likely that Edwin was among them. The 6th Machine Gun Battalion was the last unit of the 4th Marine Brigade to come home, leaving Brest on July 24, 1919 on the USS Santa Paula and arriving in Hoboken, New Jersey on either August 4 or August 5, depending on whether the history books or the stamps on the travel records are more accurate. The Santa Paula was a steamship built for commercial freighter service in April 1917. The ship was requisitioned by the US Navy for war service in August 1918, and on August 21, 1919 it was decommissioned and returned to the original owners (Wikipedia). Edwin was promoted again shortly before leaving France. The July 1919 muster roll says "July 10-Pmt’d to the rank of Sgt, to rank as #1 fr same date. Auth Bn Comdr." After their arrival in the U.S., the Fourth Brigade participated in a parade in New York City on August 8. On the same day, the brigade was transferred to the naval service upon its arrival at Quantico, Va. On August 12, 1919, the brigade was reviewed by the President in a parade in Washington, D.C. (McClellan page 79).

The 4th Marine Brigade was demobilized on August 13, 1919, and the August muster roll records the discharge of Edwin Beach and many other men on that date. It says “13-For the convenience of the Gov’t. Auth Par 5, M.C.O.31, c.s., Character: Excellent." Edwin went back to his job at the railroad after his discharge from the Marines. On October 3, 1928 he eloped with the foreman's daughter, Ruby Jarrell. Ruby was a few months shy of being old enough to marry without her parents' permission, so she lied about her age in order to get married, a fact which greatly amuses her descendants. The couple lived in Canton, Ohio and had several children, living a normal life until Edwin's death on February 17, 1942. Ruby lived on for another 68 years, dying on April 23, 2010 at the age of 102. |

||||||||||||||||||||

Edwin's uniform and other military paraphernalia were on display for several years in the 1980s and 1990s at the now-defunct Ohio Society of Military History museum in Canton, Ohio. At some point in time, the uniform had been taken apart with the intention of using the cloth to make a quilt. But fortunately, Ruby Beach was a notorious procrastinator with projects like that, and the quilt was never made. In the 1980s, Edwin and Ruby's son Jerry started exploring his father's military history, and he hired a seamstress to put the uniform back together. He obtained some of the documents used in this article. It was also at his instigation that Edwin was awarded the Purple Heart in 1989 for his encounter with mustard gas at Belleau Wood in 1918. Two of the pictures above were "borrowed" from the internet, and it's likely that they originally belonged to Jerry Beach (thank you). The newspaper article at left has more information. The Marines' dark green uniforms were disliked by the other Allies. They were too close to the color of the German uniforms, and created a risk that the Marines would be shot by their own side in a case of mistaken identity - or that German troops might not be immediately recognized for what they were. In addition, clothing was in short supply during the war and new Marine uniforms simply weren't being shipped to France. When the Marines' original uniforms wore out (which took about two months), they were issued Army uniforms to wear as a replacement (Devil Dogs page 435, US Militaria Forum). The Marine-green uniform above may have been worn during the victory parades after the war, or even during the occupation. But it's too fresh and clean - and the wrong color - to have been worn in combat. After the war, the helmet was played with by two generations of children before moving to the safety of a museum. |

The official design was picked in a contest that included Marine and Army soldiers within the 2nd Division. The shoulder patch on Edwin's uniform appears to be made from tent canvas. The emblem was also painted on the front of his helmet, which can be seen in the pictures in the previous section. It doesn't meet the regulations for the approved design, which specified that the patch for the 6th Machine Gun Battalion was a purple oval with the star and Indian head inside. US Militaria Forum has an excellent multi-page article about the star and Indian head insignia, and there are forum posts about other aspects of the uniform and equipment in a different discussion. The image on the right side shows several variations of the "regulation" shoulder patch for the 6th Machine Gun Battalion, from page 3 of the US Militaria Forum article. The Marine Times also has an article on the shoulder patches.

There was also a gold wound chevron that was to be worn on the lower right sleeve, and perhaps this is the reason that Edwin’s exposure to mustard gas at Belleau Wood is listed on his war service chevron papers. This is the only document I have seen that mentions it. His discharge papers say that he didn’t receive any wounds in service, but this didn't prevent him from receiving the Purple Heart for the gas exposure several decades later. The notation about the gas on the war service chevron paper may have been enough authorization to wear the wound chevron. But in any case, he didn’t take advantage of the opportunity to wear these chevrons. The chevrons on the upper left sleeve of his uniform are his sergeant’s stripes. There was also a red discharge chevron that was to be worn midway between the elbow and shoulder of the left sleeve, pointing upward. Former soldiers were allowed to wear their uniforms freely for three months after discharge, but after this period they could be charged with impersonating a soldier if they wore the uniform in public without having the discharge chevron sewn to the sleeve (US Militaria Forum). The discharge chevron has also not been attached to Edwin’s uniform, so we can assume that he didn’t want to wear it in public. |

Edwin earned several medals during his time in Europe. The pictures above show two versions of the same picture, one with no writing so the medals can be seen clearly, and one with writing identifying what they are. The items in the case are all originals. Except for the Purple Heart (which was awarded in 1989), the medals on the uniform are copies that were acquired decades after the war. The resolution on my museum photos is too low to allow much enlargement, examination of detail, or even reading the writing on the medals. So the rest of this section uses internet photos to provide a clearer view.

The Croix de Guerre is a high French military honor, and units that have been awarded the Croix de Guerre two or more times receive the fourragere (a braided cord that is worn on the left shoulder of the uniform). The fourragere comes in several different colors depending on how many times the unit has been awarded the Croix de Guerre. The entire 4th Marine Brigade was awarded the Croix de Guerre three times for their heroic action at Belleau Wood, Soissons, and Blanc Mont, which entitled them to the fourragere aux couleurs de la Croix de guerre (green and red, the colors of the ribbon on the Croix de Guerre medal). It is part of the uniform of the 5th and 6th Marines to this day. The 6th Machine Gun Battalion was permanently deactivated after the war, but if the battalion still existed there is no doubt that the fourragere would still be part of their uniform. JOMSA has an article with more information on the fourragere. The Marines were awarded the Croix de Guerre with two palms and one gilt star (metal devices attached to the ribbon), but the example here only has one star with no palm leaves. The fourragere pin seems to be a very rare item. I was only able to find three websites that mentioned it, a museum site, Wikimedia Commons, and an auction site. None of them explained what it was for, but apparently it was designed to be pinned to the ribbon of the Croix de Guerre medal.

The United States victory medal was awarded to all military personnel for service between April 6, 1917, and November 11, 1918. The other Allied nations issued a similar medal to their troops using the same ribbon and an image of winged victory on the disc, but with some variations in the design. In addition, the Army and Navy each issued their own battle clasps (metal bars that attached to the ribbon) to signify participation in specific battles. Wikipedia lists the available battle clasps, and says that the medals issued to the Marines had a Maltese Cross affixed to the ribbon. The 2nd Division (including the 4th Marine Brigade) received five battle clasps:

The Defensive Sector clasp apparently includes Belleau Wood, which was not given a clasp of its own and was not considered to be part of the Aisne defensive, even though the Aisne defensive and Belleau Wood were an uninterrupted sequence of events that simply had different names assigned to different segments. This is apparently part of the Army's policy of classifying Belleau Wood as a local engagement instead of a major offensive. I can see nine bars/clasps in Edwin's medal case, but I can't read the writing on them and don't know if the extras were duplicates or if they were something else. Bars/clasps were issued for other purposes too. Prior to December 1945, four years of honorable service without getting into trouble were required to get a good conduct medal in the Marines. But most branches of the service change the requirement to one year of service in time of war, and the Marines must have done this in World War I. Several of the medals in the case were not issued by the military, and it took some detective work to figure out what they were. Some of the "extra" clasps in the medal case may belong to the unofficial French medals, since these are often pictured with a name clasp on the ribbon similar to the battle clasps on the Victory medal. Wearing these unofficial medals on the uniform is prohibited. The Verdun medal was created by the Verdun City Council in November 1916, originally to be awarded to those who served on the Verdun front between February 21, 1916 to November 2, 1916. It was later extended to those who served anywhere in the Argonne and St Mihiel sectors between July 31, 1914 and November 11, 1918. There were several variations of this medal, and Edwin's appears to be the "Vernier" model (Museums Victoria Collection, Hendriks Medal Corner). The St. Mihiel medal was created by the town of St. Mihiel in 1936 to recognize the American soldiers who fought to liberate the town in 1918 (GWPDA). This was nearly 20 years after the war, and the medal didn't just automatically arrive in the mail; recipients had to apply for it. JOMSA explains more of the history behind this medal. The American Legion one is a bit of a mystery. It appears to be an American Legion membership badge attached to a ribbon, but the history behind it is unclear. These ribbons were apparently issued to officers of the American Legion, but it's not clear whether anyone else got them in this same form. There are some American Legion awards that use the same ribbon with a different medal. The American Legion is a serviceman's organization created immediately after World War I, primarily to serve the returning veterans. The Army of Occupation of Germany medal has a strange history. It was created in November 1941 in response to rising tensions with Hitler's Germany, and issued retroactively to service members who performed occupation garrison duty in between November 12, 1918 and July 11, 1923. This medal is on the uniform but not in the case of original medals, and Edwin apparently didn't have physical possession of this medal in his lifetime. The Purple Heart is a combat decoration awarded to members of the US Armed Forces who are injured by an instrument of war in the hands of the enemy. Edwin's exposure to mustard gas in Belleau Wood wasn't officially acknowledged at the time it happened, but he was awarded the Purple Heart for it in 1989. History of the US Army and the USMC & USN Reenactors Association have information on USMC dog tags in World War I.

A photo from Together We Served has an additional medal that wasn't there when my pictures were taken. It appears to be a Marksman badge in a later style, with two additional clasps attached. According to Wikipedia and this USMC booklet, the badge style used by the Marines during World War I was a simple 2"x½" bar with the word "Marksman" on it. Edwin's original badge appears to be face down in the medals case in my picture. The recipient's name was engraved on the back of marksmanship badges, and even though the picture quality is poor I can see some markings on the side that's facing up. |

|

|

There is another World War I veteran in the family who seems to have mostly been forgotten, so let's take a moment to remember him here. John Floyd Herbert (known as Uncle Floyd in my branch of the family) was in the AEF from June 12, 1918 to February 3, 1919. From July 25, 1918 to his discharge on March 10, 1919 he was in Company C of the Army's 7th Infantry Regiment in the 3rd Division. This regiment also served at the battle of Belleau Wood, which ended on July 26; based on the dates, it looks like Floyd was transferred into this unit as a replacement for one of the men who was lost there. Floyd served in three of the same battle sectors as Edwin - Aisne-Marne, St. Mihiel, and Meuse-Argonne - and was "slightly" wounded in action on October 3, 1918, which was during the Meuse-Argonne engagement. He was later discharged with a 10% disability. But the wound was more serious than the records indicate. When he died in 1921, his death certificate said that the cause of death was a brain abscess caused by being shot in the head in France. He never married or had any children, so he has no descendants to honor his memory. Floyd Herbert and Edwin Beach probably didn't meet in France. There was no family connection at the time - in 1918, Ruby Jarrell (Floyd's niece and Edwin's future wife) was a 10 year old girl living in West Virginia with her parents and siblings, and Edwin obviously hadn't met her yet. The men were serving in different divisions, so it's unlikely that their duties would have brought them together. |

|

Other family history articles: |

|

Article by Edwin Beach's granddaughter Carolyn H. Written in 2019, the centennial of the year his service ended, and updated in subsequent years. |